When we think about a child’s success in literacy and numeracy, we often credit good teaching, a supportive home environment, or strong effort. While these factors are undeniably important, a groundbreaking study suggests there’s something else playing a powerful role—genetics.

A 2013 study published in Psychological Science by Kovas et al. revealed a surprising insight: In early primary school, literacy and numeracy skills are more strongly influenced by genetics than general intelligence (IQ).

This finding has major implications for how we think about teaching and learning, and it offers valuable lessons for parents, teachers, and education policymakers.

What Did the Study Find about literacy and numeracy?

Researchers studied over 7,500 pairs of twins in the UK between the ages of 7 and 12. They measured the children’s abilities in:

- Literacy (like reading and writing)

- Numeracy (mathematics)

- General cognitive ability (commonly known as “g” or IQ)

At ages 7 and 9, they found that:

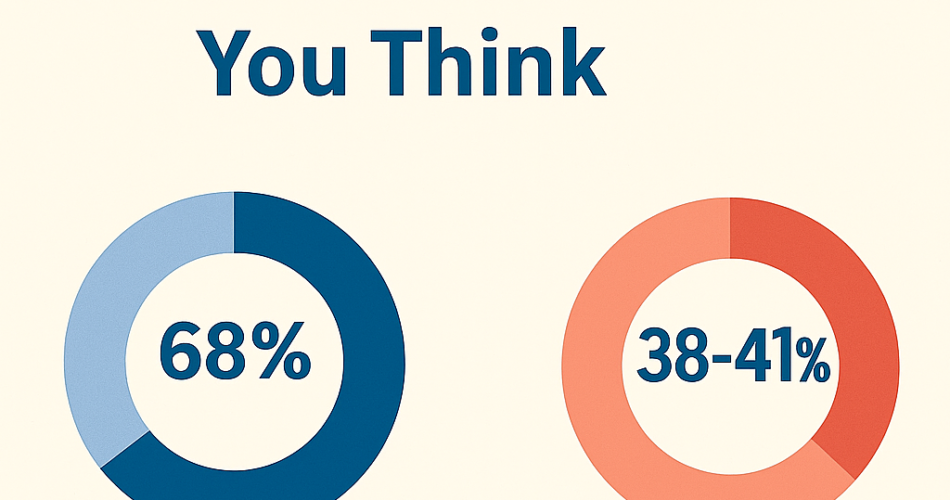

- About 68% of the differences between children in literacy and numeracy were explained by genetic factors.

- In contrast, only around 38–41% of differences in general intelligence were due to genetics at that age.

By age 12, this gap narrowed, and the heritability of general intelligence increased—suggesting that as children grow, genetics plays a bigger role in shaping their cognitive development.

Why Would Reading and Math Be More Heritable Than Intelligence?

It might sound counterintuitive. After all, we expect IQ to be something you’re “born with,” and literacy/math to be things you learn.

But here’s the twist: universal schooling gives most children access to similar instruction in reading and math during the early years. That means the environmental differences (like school quality or teaching style) are smaller. When the environment is equalized, genetic differences become more visible.

In contrast, general intelligence isn’t taught in a structured way. It’s shaped by a child’s day-to-day experiences, language exposure, play, family dynamics, and even chance. This creates more environmental variability, reducing the apparent role of genetics in early IQ differences.

What This Means for Parents and Teachers

1. One-Size-Fits-All Teaching Isn’t Enough

While early education may seem equal, children’s genetic makeups make them learn differently. Some grasp reading quickly, others excel in numbers, and some need more time or a different approach. Schools should embrace flexibility and personalization in how they teach core skills.

2. Struggling Readers and Math Learners Aren’t Lazy or “Less Smart”

Genetics isn’t destiny, but it does influence how easily a child picks up a skill. Instead of blaming children or lowering expectations, we need to recognize individual learning patterns and offer the right support.

3. Early Support Can Make a Big Difference

Even if genetics plays a strong role, early intervention still matters. Just like athletic talent needs training, natural learning strengths flourish with guidance. Likewise, kids who face genetic challenges can improve significantly with the right help.

4. By Age 12, Intelligence Becomes More Influenced by Genetics

As kids grow older, they begin to seek and shape environments that match their abilities. This is called gene–environment correlation. It means that a student’s natural interests and aptitudes will guide their learning choices—so providing a wide range of learning opportunities is essential.

What Should Educational Institutions Do?

- Adopt Adaptive Learning Tools: Technology can help tailor learning to each student’s pace and strengths.

- Provide Training for Teachers: Educators should be equipped with knowledge about learning diversity, including how genetics and environment interact.

- Support Data-Informed Education: Ongoing assessment helps identify learning needs early and accurately.

- Avoid Labeling Students Too Early: Just because a child struggles in math at 7 doesn’t mean they can’t excel later. Focus on growth, not fixed ability.